This coming week, religion scholars from all over the world descend upon Erfurt, Germany, for the quinquennial conference of the International Association for the History of Religion (IAHR). I am writing this post from the comfort of a Deutsche Bahn train seat, on the last stage of a long journey from Santa Barbara. It will be a busy week: I am personally involved with three panel sessions, giving a paper in two of them and assuming the duty of co-organizer of all three. On Monday morning we will have a fun and interesting session on conspiracy theories and contemporary religion, co-chaired by David Robertson and myself; Tuesday afternoon, we have a very promising session called “After Deconstruction”, co-organized by Ann Taves and myself; and on Thursday, there is a panel on “secrecy” conceived of by Christinane Königstedt, with me as co-organizer and a speaker as well.

This coming week, religion scholars from all over the world descend upon Erfurt, Germany, for the quinquennial conference of the International Association for the History of Religion (IAHR). I am writing this post from the comfort of a Deutsche Bahn train seat, on the last stage of a long journey from Santa Barbara. It will be a busy week: I am personally involved with three panel sessions, giving a paper in two of them and assuming the duty of co-organizer of all three. On Monday morning we will have a fun and interesting session on conspiracy theories and contemporary religion, co-chaired by David Robertson and myself; Tuesday afternoon, we have a very promising session called “After Deconstruction”, co-organized by Ann Taves and myself; and on Thursday, there is a panel on “secrecy” conceived of by Christinane Königstedt, with me as co-organizer and a speaker as well.

Unfortunately, since there is an enormous amount of parallel sessions at this conference I am missing out on a lot. Including, as it turns out, some extremely interesting cognitive science of religion panels. If I were not discussing conspiracy theories on Monday morning (a perfectly normal way to start a week), I would certainly have gone to this exciting panel on recent innovations in the experimental study of religion. Some of the leading new experimentalists from the MINDLab in Aarhus (Jesper Sørensen, Uffe Schjødt, Kristoffer L. Nielbo) will be discussing an emerging neurocognitive paradigm that I find very promising (Ann Taves and I discussed it in our forthcoming article in RBB).

At least my other two sessions are directly connected to the Occult Minds project. In the panel “After Deconstruction: Reassembling the Study of ‘Religion/s’ (and Other Dubious Categories)”, we tackle a very central question that is at once theoretical, practical, and political, and which is a major backdrop for the “building block approach” (BBA) that Taves and I have been developing in recent publications. We have convened four papers on four problematic categories that have all faced the issue: “Gnosticism” (Dylan Burns), “magic” (Bernd-Christian Otto), “esotericism” (Asprem), and “religion” (Taves). Burns’ opening paper on Gnosticism will provide a context for the rest of us: this category was dismantled by specialists already in the 1990s. Now, two decades later, we are in a position to say something about the effects of this move – including unintended consequences. From there we move to Otto, who together with Michael Stausberg has made an argument (here) about the concept of “magic” that bears some similarities to what Ann and I are arguing in terms of building blocks. In my own paper I will reflect a bit closer on what consequences I see my recommendations (in the forthcoming article, “Reverse-Engineering ‘Esotericism’”) for a building block approach to “esotericism” having for the status of the category itself. Ann will close the panel with practical reflections on the consequence of dismantling “religion” for teaching “it” in departments of “religion” (basically: no need to worry!).

The secrecy panel should also be interesting. Not only is secrecy a sexy topic, but we will also have Henrik Bogdan talk about the threats of punishment in the oaths of Freemasonry. My own paper is based on research I am doing (or more precisely, theory that I am trying to develop) on the epidemiology of representations applied to various aspects of “esotericism”. The updated title of my talk is “When Secrets Travel: Reflections on an Epidemiology of Secretive Representations.”

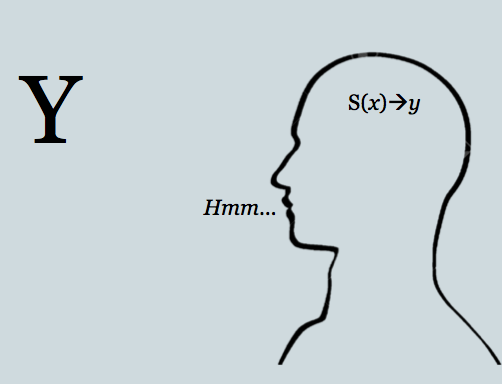

Secrecy is a paradoxical social phenomenon, as sociologists have known at least since Georg Simmel. It is, on the one hand, about restricting and controlling (strategically relevant) information; on the other, “secrets” are highly desirable commodities that can travel fast in the shape of e.g. rumours and moral panics. In the paper, I try to elaborate some cognitive points on top of the excellent sociological work that already exists.

In fact, most of what is worth saying about secrecy was already said by Simmel in his remarkable 1906 paper on “The Sociology of Secrecy and of Secret Societies”. On re-reading it recently, I was struck by how much of his discussion is grounded in a micro-sociological account that draws directly on the cognitive and psychological situation of interacting agents (e.g., how much do people know about each other? What is the relation between this information, decision-making and action?). I try to reclaim some of this perspective, focusing especially on how secretive representations rely on metarepresentational abilities – e.g., the ability to represent x (whatever it means) as a secret, or attribute some secret to person A, or infer some hidden content x behind representation y. I will go on to argue that when we see this structure in light of Dan Sperber’s epidemiology of representations, we should not be surprised to find, historically, that claims of secrecy are associated not only with social processes of individualization, social differentiation, stratification, the creation of cultural capital etc., as sociologists have demonstrated, but also with cultural innovation. The arcanum, being deliciously unknowable in principle, is always open for new interpretations.

And with that, my train is arriving in Erfurt.